Artificial intelligence (AI) can speed up and sometimes outperform clinicians in a variety of tasks and is beginning to be integrated into day-to-day patient care

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) is growing across medicine, particularly in the diagnosis of diseases. Traditional diagnostic approaches are manual and time consuming, for example, reading patient scans is a slow, skill-intensive process and there is a growing shortage of radiologists in the UK to do this work. Using AI can aid clinical decisions and support clinicians by enabling more consistent care delivery across different healthcare settings and freeing up time for other work.

In the same way that doctors learn through education, assignments and experience, AI algorithms – processes or sets of rules for problem-solving operations – must learn their jobs, by being fed data or scans and learning to recognise patterns, analyse data such as medical images and make decisions.

The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) supports AI innovation and technology from concept to NHS adoption and rollout, through prototype development and real-world testing in health and social care settings.

Predicting drug success for cancer patients

Researchers at The Institute of Cancer Research in London, funded by the NIHR, have created a prototype test that can predict which drug combinations are likely to work for cancer patients in as little as 24-48 hours. They use AI to analyse large-scale data from tumour samples and can predict patients’ response to drugs more accurately than current methods.

Analysing the genetic makeup of tumours can reveal the mutations that encourage growth, and some of these can be targeted with treatment. This alone is not enough to select drug combinations, and the new test also examines molecular changes in the tumour, and how they interact with each other in response to treatments.

The AI works in two stages, first by predicting how cells are to individual cancer drugs, looking in particular at three genetic markers, and then predicting how they will respond to combinations of two drugs.

It can process information quickly, turning around results in just two days, and has the potential to guide doctors on which treatments are most likely to benefit individual cancer patients.

Reducing COVID-19 spread in hospitals

At the University of Oxford, a tool has been developed, that can rule out COVID-19 infection within an hour of people arriving at a hospital. It is far quicker than the 24 hours required for a PCR test, and more reliable than lateral flow tests. Better yet, it uses only the data that is already collected within a patient’s first hour in hospital.

When people arrive in hospital their body temperature, blood pressure and heart rate are measured and blood is taken. The AI tool was trained using this information from 115,000 patients along with their PCR test results to say whether they had COVID-19 or not.

Its performance was then evaluated by estimating the COVID-19 status of all patients arriving at two hospitals’ over a two week period. Of over 3,300 patients arriving in the emergency department and 1,715 patients who were admitted, the AI agreed with the PCR test nine out of ten times, and was 98% accurate at ruling out COVID-19.

The software could be used to reduce the spread of the virus in hospitals and speed up treatment for people who are not infected with the virus. It is being tested in more hospital settings to evaluate how well it works in real world hospital conditions. This research was supported by the NIHR.

Continually improving care

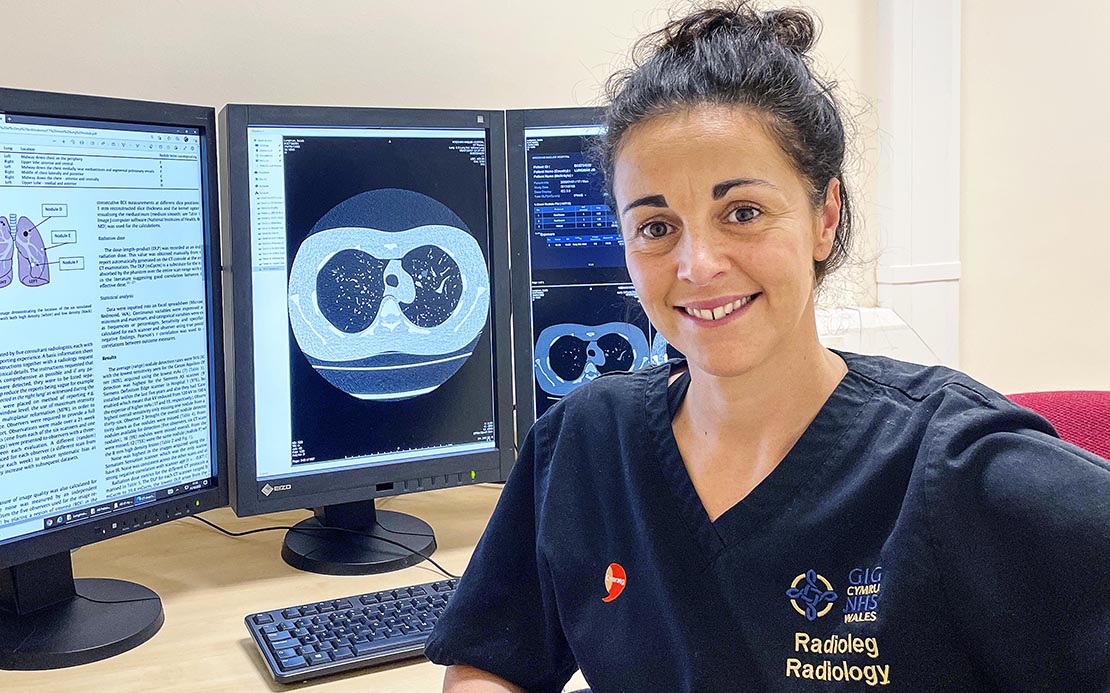

Dr Jenna Tugwell-Allsup is a research radiographer at Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board in North Wales, who has long championed research as a way to help patients. Her past work revealed that giving patients a video clip to watch with information explaining what an MRI scan involves, what noise to expect, and the importance of staying still. She found that this video was more effective in reducing patients’ anxiety than providing written information.

Her current research focus is on AI including the MIDI trial, which is investigating whether an AI tool can identify abnormalities on MRI head scans. The AI tool is being developed and tested on patient head scans as well as healthy volunteers’ scans to teach it to identify abnormalities more quickly so that these can be prioritised for assessment by a clinician. She has also received funding to conduct a study to determine if an AI algorithm can reduce time to diagnosis of lung cancer by retrospectively assessing the chest x-rays of known lung cancer patients.

Jenna has set up a local AI Working Group within Radiology and will be collaborating with other similar groups to streamline the process of working with AIs.

“Research pushes the barriers of what we think we know. Just because we are doing something well, doesn’t mean we cannot do it even better. I hope my research has guided and influenced others in radiography to think critically about the way we work and how we can continually improve care.”

– Dr Jenna Tugwell-Allsup

AI studies

Because AI technologies can analyse datasets and scans in seconds, there is great value in training them to read patient scans and assist in diagnosis and predicting the best treatments. The NIHR is currently funding trials to see if algorithms can support pathologists in reading images of prostate cancer biopsies, help to reliably identify coronary artery disease by reading the imaging used to diagnose it, and to correctly recognise ‘glue ear’, a common childhood ear infection where the empty middle part of the ear canal fills up with fluid. This condition is also known as otitis media with effusion, and can cause hearing impairment and disability.

The NIHR ensures that patients and clinicians are actively involved in the development of these new tools so that they can be implemented in practical settings across the NHS. This also ensures that they are designed to mitigate the potential for bias in these algorithms - both in terms of the data they are trained on but also any incorrect assumptions as to how accessible they will be by less privileged groups.

How you can get involved with research

Sign up to Be Part of Research to be contacted about a range of health and care research. Or check out our full list of studies to see if one is right for you.

And if taking part in a study doesn’t feel right at the moment there are other ways to get involved in research.