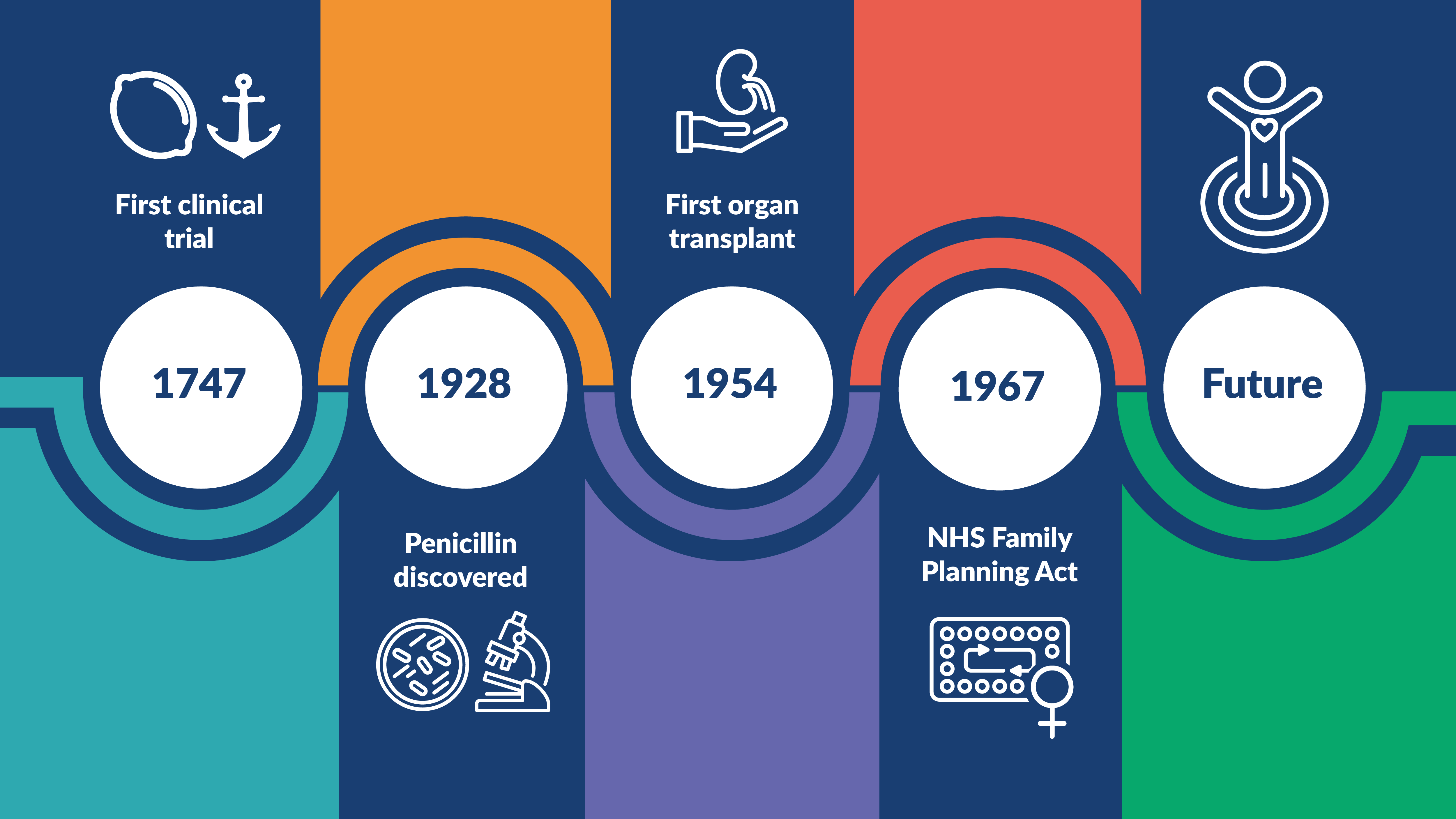

Healthcare research has come a long way in the past few hundred years, from simple observations to modern large scale intervention studies involving thousands of participants. Every day, healthcare professionals and scientists find new and improved ways of screening, preventing, diagnosing and treating illnesses, as well as organising and delivering services.

Health and care research is only possible because volunteers come forward to take part in research. These volunteers can be patients or healthy individuals. Without carefully designed research studies, most of the advances in healthcare over the last 200 years wouldn’t have happened.

But before you can see whether a treatment, drug, or technology works, it has to be discovered first. That means there is a lot of research undertaken before clinical studies can take place. Usually, discoveries involve years of dedicated work; but from time-to-time they occur by chance, building on the body of dedicated research. Here are a few examples of some of the most important research that has shaped modern healthcare.

The first clinical trial

One of the earliest clinical trials was conducted in 1747 by James Lind, a Scottish doctor and a pioneer of naval hygiene in the Royal Navy. At the time, a disease called scurvy was a huge problem for sailors and Lind wanted to investigate whether citrus fruits could cure it.

He selected 12 patients with scurvy on a ship, divided them into 6 pairs, and gave different treatments to each over the course of a week. The treatments included drinking cider, vinegar or sea-water, or eating citrus fruits.

The sailors whose daily diet included citrus fruits recovered, therefore proving that citrus fruit could cure scurvy.

Now clinical trials are used to test the safety and effectiveness of all kinds of treatments and health improvement solutions.

The first use of a placebo in a clinical trial

In medicine, a placebo is a treatment that seems real to the patient, but doesn’t actually have any therapeutic effect. They have become a powerful tool in healthcare research, making it easier to assess the genuine impact of a treatment.

In 1863, an American doctor called Austin Flint used one for the first time in a clinical trial. He gave 13 patients a placebo treatment for rheumatism. He then compared the results with trials of an actual treatment from the time.

Surprisingly, Flint found there was no significant difference between the results of the actual treatment and his placebo remedy in 12 of the cases.

The first antibiotic

Penicillin is one of the most well-known antibiotics and can be used to treat a wide range of bacterial infections.

It was first discovered by Alexander Fleming, a Scottish doctor, in 1928. He spotted when mould grew on a plate of bacteria, there was a clear area around the mould where bacteria could not grow.

It wasn’t until 1939 that his findings were confirmed. A team of scientists, including Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, purified the substance and tested it on mice. By 1941, they were ready to test it on human patients.

Working with a doctor called Charles Fletcher, the team began a set of small-scale trials. Their first subject was a policeman called Albert Alexander, whose wounds from a bombing raid had become seriously infected. Following treatment with penicillin, he began to make a recovery. Sadly, supplies of the drug ran out before his cure was complete, and he relapsed and died.

This, and tests on other seriously ill patients, showed the drug had huge potential to save lives, so it was quickly put into mass-production. The antibacterial effects of penicillin would go on to save thousands of soldiers during the Second World War.

Today, penicillin is one of the most common types of antibiotics the NHS uses to fight infections and help patients recover quickly.

The first organ transplant

When an organ is badly damaged, an organ transplant is sometimes needed to save a patient’s life. Doctors experimented with this as early as the 18th century, but they weren’t able to do it successfully until the 1950s.

In 1954, Doctor Joseph E. Murray from Boston in the USA successfully transplanted a healthy kidney from Ronald Herrick to his twin brother, Richard.

By the 1960s, doctors were performing liver, heart, and pancreas transplants. In the 1980s, they had also found a way to transplant lungs and intestinal organs.

The discovery of drugs that suppress the body’s immune system and prevent it rejecting new organs allowed more organ transplants and a higher survival rate. Thanks to this, these procedures are now far safer and more successful than in those early days.

The first contraceptive pill

Today, contraceptives give women a great amount of control of their reproductive health, but it took many years of medical research to ensure they were safe and effective.

The first large-scale human trial of birth control pills took place in Puerto Rico in 1956. It wasn’t until the following decade that they were approved for use in the UK. In 1960, hundreds of women from Birmingham and Slough volunteered to test the effectiveness of a contraceptive pill in a large-scale study. After this research showed positive results, the UK government approved its use.

Initially, the pill was only prescribed to married women. It was made available to all women in 1967.

Health and care research today

Today, the research that’s carried out into health and social care is very wide ranging. It still involves clinical trials of new drugs or surgical techniques, but also focuses more broadly on our wellbeing and quality of life.

Research can also look at the best way and best place to provide health and social care – be that in a hospital, a doctor’s surgery or our own homes. Thanks to the work of the early pioneers, we are all living longer and healthier lives. But there is always room to do more, and so more research will always be needed.

How you can get involved with research

Sign up to Be Part of Research to take part in a range of health and care research. You can also visit our 'How to take part' page to find out more about research trials that are happening now and in the future.

Our 'what happens on a study' page provides more information on how trials work. And if taking part in a study doesn’t feel right at the moment, there are other ways to get involved in research.